A domestic Xiamen Airlines flight was hijacked whilst en route to Guangzhou on 2 October 1990. The sole perpetrator, Jiang Xiaofeng, was a young man seeking to escape justice by claiming asylum in Taiwan; his actions resulted in three aircraft being destroyed on the ground, making it one of the worst air disasters in history. On the 30th anniversary of the tragedy, Alejandra Gentil revisits the incident and points to the perils involved when hijacking is used as a political tool by rival governments.

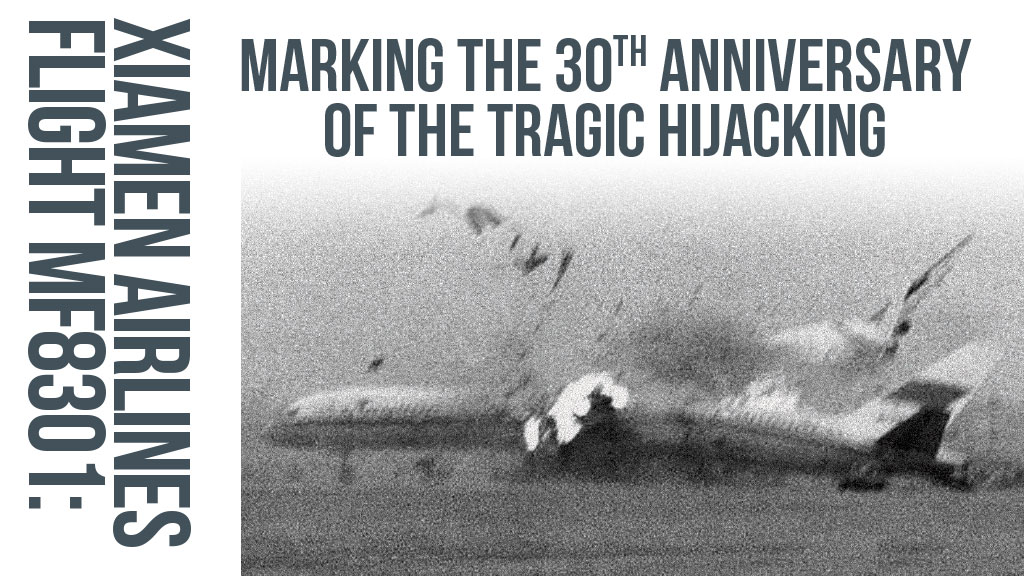

The hijacking of Xiamen Airlines flight MF8301 has gone down as one of the worst air disasters in history. Images of the aircraft colliding with two others on the ground, of passengers covered in firefighting foam being pulled out of wreckage and staff running for their lives across the apron of Guangzhou’s Baiyun International Airport are still extremely harrowing, even 30 years later. Reviewing the circumstances that led to the tragedy reminds us that terrorists are not the only foe civil aviation faces. Criminals, asylum seekers and, more crucially, international politics play a prominent role in acts of unlawful seizure of aircraft.

The Hijacking

On the morning of 2 October 1990, Xiamen Airlines flight MF8301 departed from its hub in Xiamen at 6.57 a.m. on what was supposed to be a short domestic trip to Guangzhou. Among the 93 passengers and 9 crewmembers on board was Jiang Xiaofeng, a young man seated in row 16, who was wanted by the police on charges of embezzlement. He had reportedly stolen 17,000 Chinese Yuan (at the time amounting to around USD $3600) from his company and was seeking to escape justice by claiming asylum in Taiwan. He would never reach his intended destination.

Shortly after take-off, Jiang made his way towards the flight deck. Reports differ on how he actually gained entrance to the cockpit – Time magazine claimed he was holding a bouquet of flowers as a Moon Festival offering to the flight deck crew and was thus allowed to enter, while Flight Safety Digest cites a Chinese news outlet indicating that the hijacker forced his way in, pushing aside the male flight attendant who tried to stop him. These were pre-9/11 days, prior to reinforced cockpit doors and standards on lockdown measures being implemented, so the flight deck was more easily breached. Once inside, he ordered everyone out – except for the captain – and threatened to detonate explosives allegedly strapped to his body if the aircraft was not diverted to Taiwan. Thus started the hijacking that would turn out to be the deadliest in the history of China’s civil aviation industry.

The hijacked aircraft never made its way to Taiwan, but instead continued towards its original destination, Guangzhou. Why the pilot, Cen Longyu, decided this is not known, but it is most likely linked to politics. Taipei’s airport lies a short hop away from Xiamen, about 800km to the east. It would have certainly been technically feasible to fly there. However, the pilot did not change course and continued southwest onto Guangzhou’s Baiyun Airport. Some sources say the pilot talked the hijacker into flying to Hong Kong, a short distance away from Guangzhou, on the grounds that there was not enough fuel to get to Taiwan. The New China News Agency, however, never mentioned this and instead pointed its finger at the airline’s policy when stating that the incident “revealed the existing problems of the airport and airline company”. Standard airline policies of that time normally called for the crew members to cooperate with hijackers in order to ensure the safety of all on board.

“…Xiamen Airlines flight MF8301 departed from its hub in Xiamen at 6.57 a.m. on what was supposed to be a short domestic trip to Guangzhou. Among the 93 passengers and 9 crewmembers on board was Jiang Xiaofeng, a young man seated in row 16, who was wanted by the police on charges of embezzlement…”

It can only be speculated that changes to this policy were triggered by the 1988 hijacking of another Xiamen Airlines flight on the same route, an inopportune action which would have grave consequences. Based on the presumption that the safest place for a hijacked aircraft is on the ground, Air Traffic Control and airport authorities should cooperate with the hijacked aircraft, maintain open lines of communication with it and afford it landing permission when requested, clearing the flight paths, runway and taxiways.

In this case, it appears the pilot intentionally deceived the hijacker, who did not know his demand to fly to Taiwan was not being met until the end as communications with the ground were cut. Once the aircraft reached Baiyun Airport’s airspace, it circled over it for 40 minutes before running low on fuel. At this point, radio communications with the ground were re-established. Chinese authorities then authorised the aircraft to land at any airport within or outside the borders of China’s mainland, including Taiwan, in order to ensure the safety of the passengers and crew on board. Reading between the lines, the authorities were sanctioning the aircraft to fly to Taiwan without fear of retaliation or interception, but with fuel running low these were now empty words. At this crucial point, only Guangzhou and neighbouring Hong Kong were an option. The commander then made the fateful decision to land in Guangzhou. Reportedly the hijacker at this point had not been aware that the aircraft had been overflying Guangzhou.

“….After a 1988 hijacking from Xiamen to Taipei and the fatal hijacking of MF8301 in 1990, there were 11 more hijackings between 1993 and 1998…”

Flight MF8301 declared an emergency and was cleared to land. On the ground, operations were handled as normal. Questions arose later as to why the runway was not cleared. A China Southern Boeing 757 with 122 people on board was awaiting clearance for take-off to Shanghai, while an empty Boeing 707 was being refuelled close by. As the hijacked B737 made its final approach and landing, the hijacker, furious at the deception and desperate to avoid landing in mainland China, struggled with the pilot. The aircraft touched down hard at 9.04 a.m. and swerved to the right. Thundering out of control, the aircraft clipped the empty B707 and rolled on, violently colliding with the fully loaded B757, breaking it in half and killing forty-six of its passengers. Flipping over, it finally came to a standstill, broken apart, engulfed in flames and wheels up. Eighty-two of its occupants lost their lives. Among them, the pilot-in-command and the hijacker, crucial determinants of the tragedy. No traces of explosives were found on Jian Xiaofeng’s body.

The Politicisation of Hijacking

The choice of Taiwan as the destination by the hijacker was obviously not a coincidence. The political tensions between Beijing and Taipei, exacerbated throughout the 1980s, included a propaganda war within which hijacking was encouraged and rewarded, each side using them for their own political gain. Taiwan maintained a policy of welcoming hijackers as “freedom seekers” and heroes against communism, providing them with asylum, jobs and money. The lure of political freedom and material gains additionally made Taiwan an attractive destination not only for political refugees, but economic migrants as well. In addition, people wanted for crimes in the Popular Republic of China (PRC) could evade prosecution by being sheltered in Taiwan. But, with the lack of political rapport between the two governments, getting there was the crux of the matter. Consequently, people who wanted to get to Taiwan from PRC either had to face dangerous boat passages or, well, hijack an aircraft.

This scenario was not new to civil aviation. In fact, it was a direct duplication of the US-Cuba wave of hijackings of the 1960s. After Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution in Cuba, a propaganda war broke out between the US and Cuba. Hijackings were also encouraged then, each hailed by both sides as small victories. This resulted in so many incidents of unlawful seizure that it was dubbed a ‘hijacking epidemic’. While the perpetrators then had either political or financial objectives in mind, or were mentally unstable, the epidemic provided the seeds of what would turn out to be branded as ‘aviation terrorism’ from 1968 onwards. Eventually the epidemic was only remedied through a combination of security measures and political will, the latter enshrined by The Hague Convention of 1970 and, most importantly, by the hijacking agreement between the US and Cuba through which extradition of hijackers was formalised between the two countries. This sent the message that hijacking was no longer acceptable by either party as a political tool and would, henceforth, be subject to severe penalties and possible extradition.

“…Thundering out of control, the aircraft clipped the empty B707 and rolled on, violently colliding with the fully loaded B757, breaking it in half and killing forty-six of its passengers. Flipping over, it finally came to a standstill, broken apart, engulfed in flames and wheels up. Eighty-two of its occupants lost their lives…”

The PRC-Taiwan hijackings followed a similar but abbreviated history. After the propaganda war of the 1980s, the geopolitical landscape began to change as the cold war ended, economic ties flourished between PRC and Taiwan, and their relations thawed. Taiwan changed its tune and enforced severe penalties for hijacking. Nevertheless, this may not have trickled down to the population, as hijacking from PRC to Taiwan took off thence. After a 1988 hijacking from Xiamen to Taipei and the fatal hijacking of MF8301 in 1990, there were 11 more hijackings between 1993 and 1998. The ‘weapons’ used were sometimes comical. In one case, when a hijacker’s ‘explosives’ turned out to be soap, a Taiwanese official exclaimed, “A bar of soap! You’ve got to be kidding. Some people say that next time you can use a toothpick to hijack an airplane”. He was proved wrong when an Air China pilot needed less than that to divert his own aircraft to Taiwan in 1998. Like the other Chinese hijackers, he and his wife, who was a passenger on his flight, claimed asylum.

As in the case of the hijacking epidemic of the 1960s, the perpetrators of the 1990s hijacking wave between PRC and China were not terrorists – they were asylum seekers or were evading criminal prosecution in the mainland. The Hague Convention of 1970 on unlawful seizure of aircraft was formulated to ensure hijackers did not find safe havens in politically friendly countries, but were instead either prosecuted or extradited to a state claiming jurisdiction over the offence. Taiwan, a signatory of the convention, tightened its position on hijacking and instead of granting asylum, it handed the perpetrators harsh sentences. However, Beijing too, claimed jurisdiction over the offences and so the political battle continued but at least the message was clearly sent that hijacking and diverting an aircraft to Taiwan was no longer a means to obtain freedom or financial gain. In fact, despite the fact that a Draft Agreement on the Surrender of Aircraft Hijackers between the two States was formulated but never signed, Taipei eventually ceded to Beijing’s pressure and agreed to repatriate the 1990s hijackers – who had already served time – to the Chinese authorities to be tried again, an act that contravenes international law.

Politics can play a big role in the proliferation of hijackings. When it is perceived as an easy way out of harsh circumstances – material, political or otherwise – political rhetoric that encourages or opens the door to hijacking opens a Pandora’s Box that more often than not ends in tragedy. When this is paired with a politicised – and thus fumbled – handling of a hijack, the conditions are created for a disaster of tremendous magnitude. Flight MF8301 illustrates the extent of the damages that playing politics with civil aviation can produce.

Alejandra Gentil has over 25 years of experience in aviation security, specialising in regulatory compliance, policy design and capacity building. She has worked extensively in AVSEC operations, consultancy and training in the Americas, the Middle East and Africa, providing technical assistance and training to airlines, airports, regulators and other aviation stakeholders.